The Extrication Of Roger Ebert

File this in the “like anybody cares now” department.

I have no idea what it is exactly that grates on me. I am daily confronted with institutional smugness from liberals, and manage to have 99.9% of it roll off my back in the dismissive acceptance that most victims of congenital elitism are merely possessed of their own, Doppelganging selves.

Then comes along a guy like Roger Ebert. Call me an elitist, but to have a professional movie-watcher trying to circumvent cinematic, theological messages for me raises my blood to earth’s-mantle temperatures.

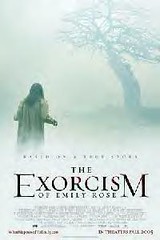

Hence my irritation at Ebert’s review of a movie I have not seen, The Exorcism of Emily Rose. I had read an interview with its director, Scott Derrickson, a professed Christian and co-writer of the script. Derrickson drew stark contrasts between his movie and William Peter Blatty’s, The Exorcist, insofar that he intends to place the audience into a position where they have to ask themselves basic questions about belief while walking out of the theatre.

And apparently, this is what seems to be the bothersome element to Ebert.

The premise is loosely based on a true story in which a parish priest is on trial for murder, in the wake of a failed exorcism on a teenage girl. The movie pans between the courtroom proceedings, and the flashbacks through the girl’s dilemma. A jury is asked to grapple with the definitional disparities between psychological diagnoses and the belief in demonic possession. Each conclusion begs for a different verdict, as each portend entirely different motivations on the part of the priest.

Sounds like a good story to me. But Roger is already afraid that the priest’s theological certainty is going to wash over even the skeptics like an Indonesian tsunami. Movie Man inaugurates his article with a classic literary technique—begin your piece with a quotation:

"Demons exist whether you believe in them or not," says the priest at the center of "The Exorcism of Emily Rose."

This not only falls within the constraints of textual safety for Ebert, but provides for him the first of many vertically-tossed self-pitched Wiffle balls to knock out of the park. Here’s the hit that would have left Roger Maris reeling:

Yes, and you could also say that demons do not exist whether you believe in them or not, because belief by definition stands outside of proof. If you can prove it, you don't need to believe it.

Roger Ebert want you to know that he’d be an heir apparent to Copernicus if he ever gave up his Cineplex heckling job. In a world of implausible scripts, ridiculous premises, and sanctimonious paeans to institutional socialism, Roger only feels the need to reorient the audience to reality when it comes to a horror film with uncomfortable questions about the devil’s power-of-attorney, but also seems to fear that any teetering faith in a godless big-bang theory may be effected by the Great Watchmaker in the sky:

The church is curiously ambivalent about exorcism. It believes that the devil and his agents can be active in the world, it has a rite of exorcism, and it has exorcists. On the other hand, it is reluctant to certify possessions and authorize exorcisms, and it avoids publicity on the issue. It's like those supporters of Intelligent Design who privately believe in a literal interpretation of Genesis, but publicly distance themselves from it because that would undermine their plausibility in the wider world.

You’d almost think this guy has a set of lecture notes ready to fulminate at a moment’s notice when asked to talk about this movie. Contrast this with his review of The Day After Tomorrow, a movie that basically says an environmental cataclysm destroys the planet because Dick Cheney is too busy planning Halliburton contracts to care. Ebert does indicate that the presentation of hailstones destroying cities and a President drawing a line through a North American diagram to “write off” the upper half to super-cooled Arctic air is ridiculous, but still neglects to ascribe to himself the same environmental/theological authority used to cast Literary Belial out of Emily's premise:

Of the science in this movie I have no opinion. I am sure global warming is real, and I regret that the Bush administration rejected the Kyoto Treaty, but I doubt that the cataclysm, if it comes, will come like this.

No opinion? Sure? Doubt? Still, Ebert manages to like The Exorcism of Emily Rose, though he has an opinion—a sure one—and one devoid of doubt to boot.

But what of this elitism that annoys me so bad? The time-honored “I don’t like what something means” deliberately interloping as “the masses will not understand it.” Thus:

A film that keeps an open mind must necessarily lack a slam-dunk conclusion. In the end Emily Rose's story does get told, although no one can agree about what it means.

And always beware the “you didn’t ask” preface. It only reinforces why you didn’t. All I know is, if I go into an A-fib while sitting next to him at the symphony, I’m going to die:

You didn't ask, but in my opinion she had psychotic epileptic disorder, but it could have been successfully treated by the psychosomatic effect of exorcism if those drugs hadn't blocked the process.

Come to think of it, let’s just keep him right where he is. At least here, he can only kill a plot, instead of put somebody under one.

<< Home